Case Study 2.2: How do OpenAI’s apps and Facebook’s AI speedup queries using vector databases?

How do OpenAI’s apps and Facebook’s AI speedup queries using vector databases?

Goal: Learn how to build efficient approximate indices for very high dimensional data

Often, applications need a cheap way to compute Approximate Nearest Neighbors (ANNs) in high-dimensional spaces.

For example, OpenAI uses text embeddings (vectors with thousands of dimensions) to find semantic connections between billions of documents. Classic hashing-based indices for exact matching are not sufficient here.

Vector Databases

Vector databases are specialized systems designed to store and query high-dimensional vectors (like OpenAI's embeddings). They enable fast similarity search even in spaces with thousands of dimensions by using ANN algorithms.

FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search)

FAISS is a popular library for efficient similarity search and clustering of dense vectors.

- Hardware: Can leverage GPUs to speed up indexing and search.

Example: Finding Nearest Neighbors in 768D

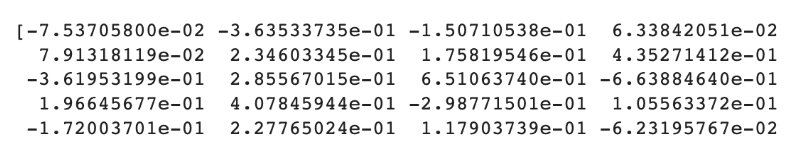

In the example below, we have a text embedding represented as a 768-dimensional vector using one AI model, Sentence-BERT. You can try your favorite AI model to generate embeddings and use them in FAISS in this Colab.

In this Python example, we first embed 1000 strings into FAISS's vector index. Then, we query for three different strings to find the approximate nearest neighbors.

import numpy as np

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

import faiss

# Create 1000 example strings

strings = [f"String {i} is making me hungry" for i in range(1000)]

# Load the SentenceTransformer model

model = SentenceTransformer('paraphrase-distilroberta-base-v1')

# Compute embeddings for the strings

embeddings = model.encode(strings)

# Create a FAISS index (IndexFlatL2 computes exact L2 distance)

index = faiss.IndexFlatL2(embeddings.shape[1])

# Add the embeddings to the index

index.add(np.array(embeddings))

# Define query strings and find their nearest neighbors

queries = ["String 42 is making me hungry",

"String 42",

"String 42 is making me thirsty"]

for query_string in queries:

query_embedding = model.encode(query_string)

# Search the index: k=5 returns the top 5 results

k = 5

distances, indices = index.search(np.array([query_embedding]), k)

print(f"\nquery_string='{query_string}' ==>")

for i, idx in enumerate(indices[0]):

print(f"Rank {i+1}: {strings[idx]}, Distance: {distances[0][i]}")

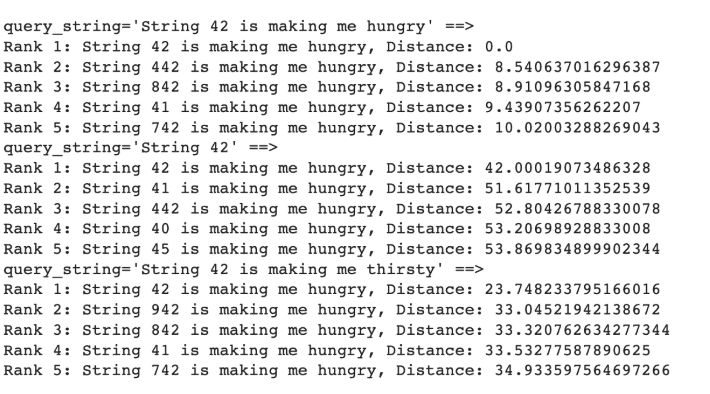

Search Results:

Observe that "String 42 is making me hungry" has an exact match (Distance: 0.0). Additionally, it discovers other related, similar strings nearby in this 768-dimensional space. Similarly, “String 42” and “String 42 is making me thirsty” do not have exact matches, but match with similar strings.

Locality Sensitive Hashing (LSH)

LSH offers sublinear-time similarity search by trading off some accuracy for speed. You can experiment with Vector Search and LSH in this Hashing Colab.

In the example below, the IndexLSH object is trained on a set of points, and then used to find approximate nearest neighbors for a new query point.

import numpy as np, faiss

# Generate 10,000 points in a 5,000-dimensional space

X = np.random.rand(10000, 5000).astype('float32')

# Build an LSH index for the points (5000 dims, 16 bits)

index = faiss.IndexLSH(5000, 16)

index.add(X)

# Find the 5 nearest neighbors of a new 5,000-dim query point xq

xq = np.random.rand(5000).astype('float32')

distances, indices = index.search(np.expand_dims(xq, axis=0), k=5)

# The search returns the indices of the approximate nearest neighbors

print("Nearest neighbor indices:", indices)

print("Distances:", distances)

In this example, the IndexLSH object is trained on the set of points, and then used to find approximate nearest neighbors for a new query point. The search returns the indices of the approximate nearest neighbors in the original set of points.

If two vectors are close together in space, they are very likely to fall on the same side of most random planes, thus sharing the same "bucket."

Comparison: Standard Hashing vs. LSH

| Feature | Standard Hashing | Locality Sensitive Hashing |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Avoid collisions (Unique buckets) | Encourage collisions (Similar items together) |

| Logic | Small input change → Massive hash change | Small input change → Small/No hash change |

| Usage | Exact lookups, Join partitioning | Similarity search, Recommendation engines |

Takeaway: LSH generalizes our indexing principles to handle modern, high-dimensional AI data, allowing us to query "closeness" rather than just "equality."