Correctness: Ensuring Safe Concurrent Execution

The Core Question 🎯

How do we know an interleaved schedule produces correct results?

Key Definitions

Foundation: Building Blocks for Correctness 🏗️

To understand how databases ensure correct concurrent execution, we need three foundational concepts:

✅ Serializable Schedule

An interleaved schedule that produces the same outcome as some serial schedule, ensuring consistency in the database.

Challenge: Harder to prove correctness—must prove same outcome for ALL possible database values

⚠️ Note: "Serializable" ≠ "Serial"

• Serial: One transaction completes before next starts

• Serializable: Interleaved but equivalent to some serial order

Don't trip up on this distinction!

🔄 Actions (Operations)

Actions in a transaction involve accessing and modifying data in a database through reads and writes.

Note: We only focus on R/W actions, not how data is modified (e.g., A-=1 or B*=10)

📋 Macro Schedules

These schedules contain only the ordering of actions. We use these for ensuring data consistency.

• Micro: Full timing, IO, locks (performance focus)

• Macro: Just R/W sequence (correctness focus)

Note: Both serial & interleaved have macro/micro versions. For simplicity, we'll call all these "schedules," and add descriptors only when needed for clarity.

Conflicts: The Heart of Concurrency Control ⚔️

Conflicts arise when transactions compete for the same data. Understanding conflicts is key to ensuring correctness:

⚔️ Conflicting Actions

Pairs of actions from different concurrent transactions where:

- Both actions involve the same data item

- At least one of the actions is a write operation

• T1.R(X), T2.W(X) are conflicting actions

• T1.W(X), T2.R(X) are conflicts

• T1.W(X), T2.W(X) conflict

Note: "conflicting actions," "conflicts," "conflict" all refer to the same thing

📊 Conflict Graph

A directed graph that represents the conflicts between different transactions in an interleaved schedule.

• Nodes represent individual transactions

• Directed edge from T1→T2 if T1's action conflicts with and precedes T2's action

Motivation: Simple data structure to help model and analyze conflicting actions

✅ Conflict-Serializable (CS) Schedules

Schedules where conflicting actions are ordered the same way as they would be in SOME serial execution (we don't care which one!).

Critical Point: Must be equivalent to at least one serial schedule - doesn't matter which serial order

Motivation: The database can choose ANY valid serial ordering that respects conflicts

Cycle Problem: If a cycle exists, there's no way to execute transactions serially without violating conflict order

💡 How to think:

• What creates conflicts? Writes!

• Can we find ANY serial order that respects these conflicts?

Refresher on Graph Algorithms 📊

Understanding conflict graphs requires familiarity with basic graph concepts. Let's review the key algorithms used in conflict-serializability analysis.

🔄 Cyclic vs Acyclic Graphs

A fundamental distinction for determining conflict-serializability:

Cyclic Graph: Contains at least one cycle - a path leads back to itself

CS Implication: Only acyclic conflict graphs represent conflict-serializable schedules

📋 Topological Sort

Algorithm to find a linear ordering of nodes in a directed acyclic graph:

Key Property: DAGs can have multiple valid topological orderings

CS Application: Each valid topological ordering represents a serial schedule that the conflict-serializable schedule is equivalent to

How to Test for Conflict-Serializability 🔍

The key question: How do we determine if a schedule is conflict-serializable? The answer is elegant and algorithmic.

📊 The CS Algorithm: Build Graph → Check Cycles

Simple 3-step test: Turn any schedule into a conflict graph and check for cycles

Step 2: Add directed edges for each conflict (Ti conflicts with and precedes Tj)

Step 3: Check for cycles

✅ Acyclic graph: Schedule is CS (topological sort gives valid serial orders)

❌ Cycle exists: Schedule is NOT CS (impossible to serialize)

🏭 Reality: What Databases Actually Do

Databases don't check CS after the fact. Instead, they prevent problematic schedules proactively:

• Use locking protocols (like 2PL) to control operation order

• Block transactions until it's safe to proceed

• Guarantee only CS schedules can occur

Example: If T1 holds a lock on A, T2 must wait to access A

→ Prevents problematic interleavings before they happen

🔗 The Beautiful Connection: Theory ↔ Practice

Conflict graphs and locking protocols work together as a complete correctness system:

• Provides mathematical framework for reasoning about correctness

• Gives us algorithmic test: "Is this schedule safe?"

• Validates that our enforcement mechanisms work correctly

Locking Protocol Enforcement:

• Implements practical mechanism to ensure only safe schedules

• No need to check every schedule—protocol guarantees safety by design

1. Conflict graphs tell us what "correct" means

2. Algorithms like topological sort let us verify correctness

3. Protocols like 2PL ensure only correct schedules happen

4. Result: Mathematically proven concurrent execution! 🎯

📚 For more depth: Transaction Scheduling & Reordering Rules

Example 1: Concert Ticket Booking 🎫

Now let's apply these concepts to a real scenario with 3 transactions and 2 shared variables.

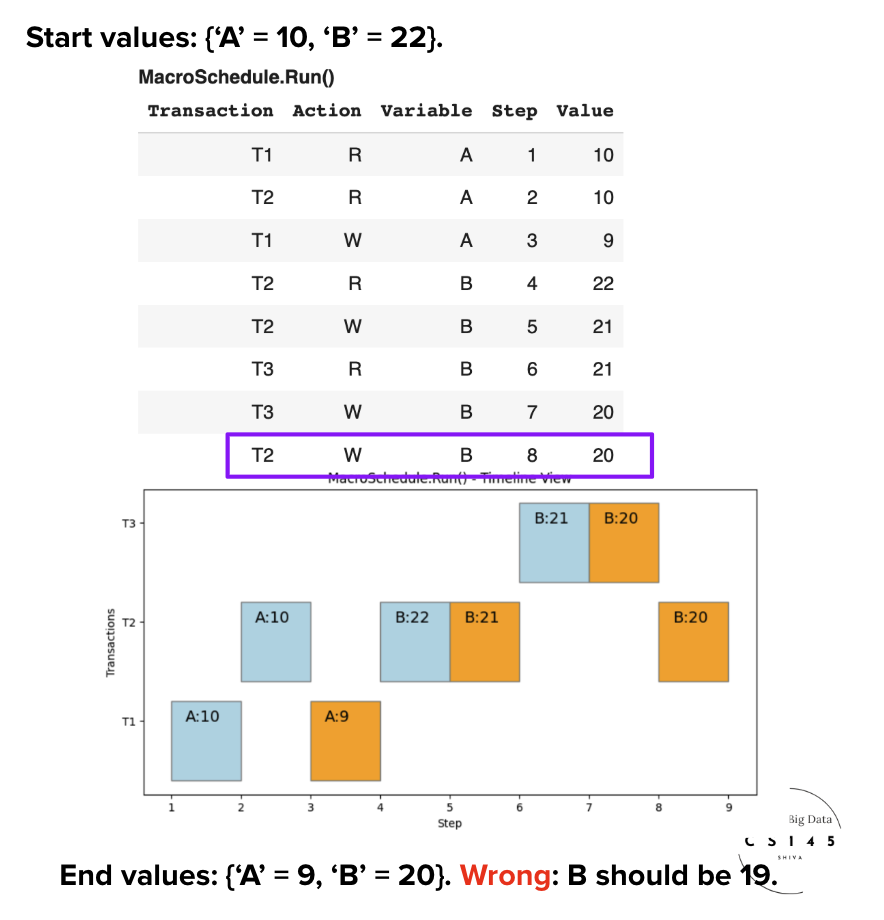

Setup: The Scenario

🎪 Scenario

Concert venue with 2 sections. Three customers simultaneously try to book tickets during high-demand sale.

• A: VIP section tickets (initially: 10)

• B: General section tickets (initially: 22)

🎭 Transaction Actions

Each customer performs specific booking operations on the shared ticket counters.

🎯 Expected Results

After all transactions complete successfully, the final ticket counts should be consistent.

• A: 9 tickets

• B: 20 tickets

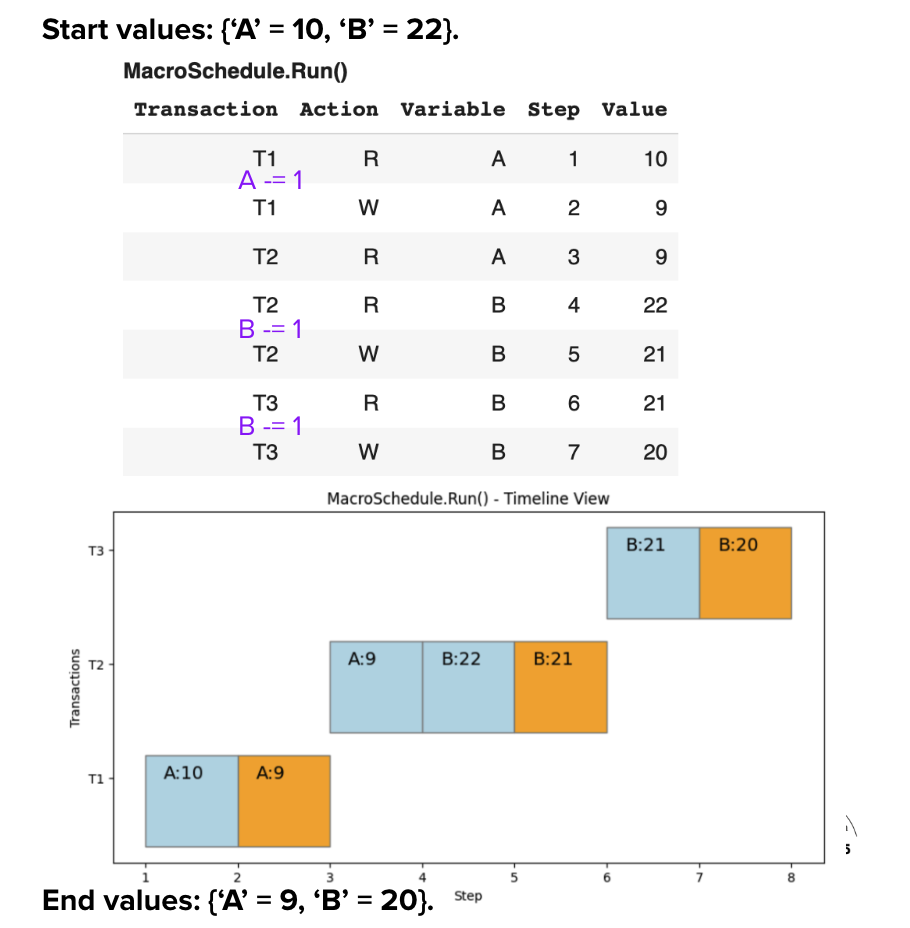

Serial Schedule S1: T1 → T2 → T3

📋 Execution Analysis

The serial schedule guarantees correctness by running transactions one at a time:

1. T1 completes: A=9, B=22

2. T2 completes: A=9, B=21

3. T3 completes: A=9, B=20

Properties: No conflicts • Predictable • ACID maintained

Conflict Identification

Conflicts happen when there are shared variables (even for Serial schedules)

⚔️ Conflict Analysis

Example Conflicting Action Pairs:

2. T2.W(B) ↔ T3.W(B) - Write-Write conflict on B (blue)

3. 4 total conflicts to track in our analysis

Key Insight: Conflicts create a chain: T1 → T2 → T3

📊 Conflict Graph Construction

Step-by-Step Process:

2. Add Edges: For each conflict, draw edge from first → second

3. Check Cycles: If acyclic → Conflict-Serializable ✅

Result: Acyclic Graph • No cycles • CS Schedule • Equivalent to T1→T2→T3

Example 2: Interleaved Schedule Analysis 🔄

Now let's explore what happens when we interleave transactions. We'll examine two different interleaved schedules to understand the difference between conflict-serializable and non-conflict-serializable schedules.

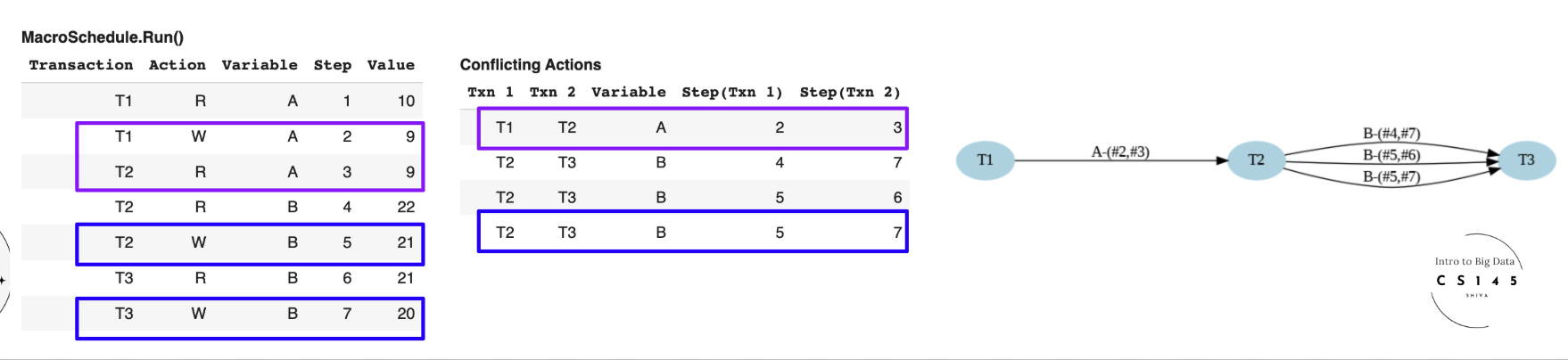

Schedule S1': Our First Interleaved Schedule

Consider S1', our 1st interleaved schedule. We can interleave the transactions while preserving correctness.

⚔️ Conflicts Identified

We compute the conflicts and build the Conflict Graph:

• Notable: B-(#4, #7) from T2 and T3

• 4 total conflicts across all transactions

Insight: The conflicts create dependencies between transactions that must be respected.

📊 Graph Analysis

We see edges for each conflict in the Conflict Graph:

✓ Conflict-Serializable: CS Schedule

✓ Multiple Valid Orders: T2→T1→T3 OR T2→T3→T1

Why Both Work: Both are valid topological orderings, meaning either serial execution produces equivalent results.

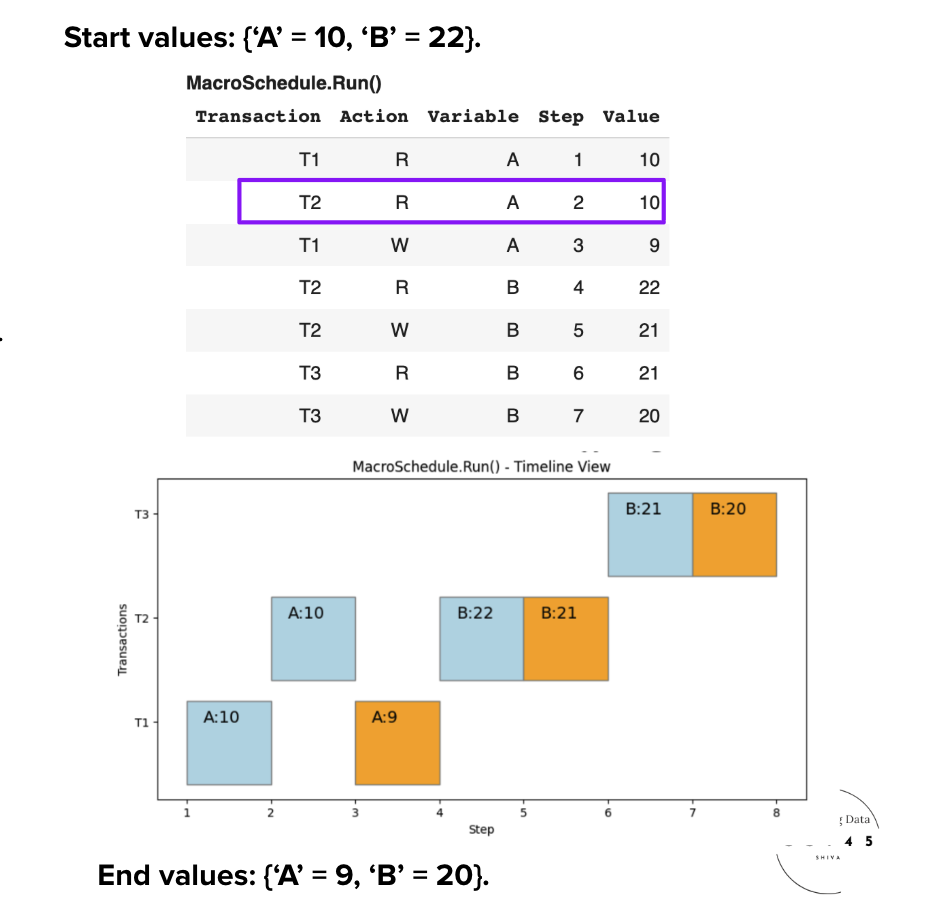

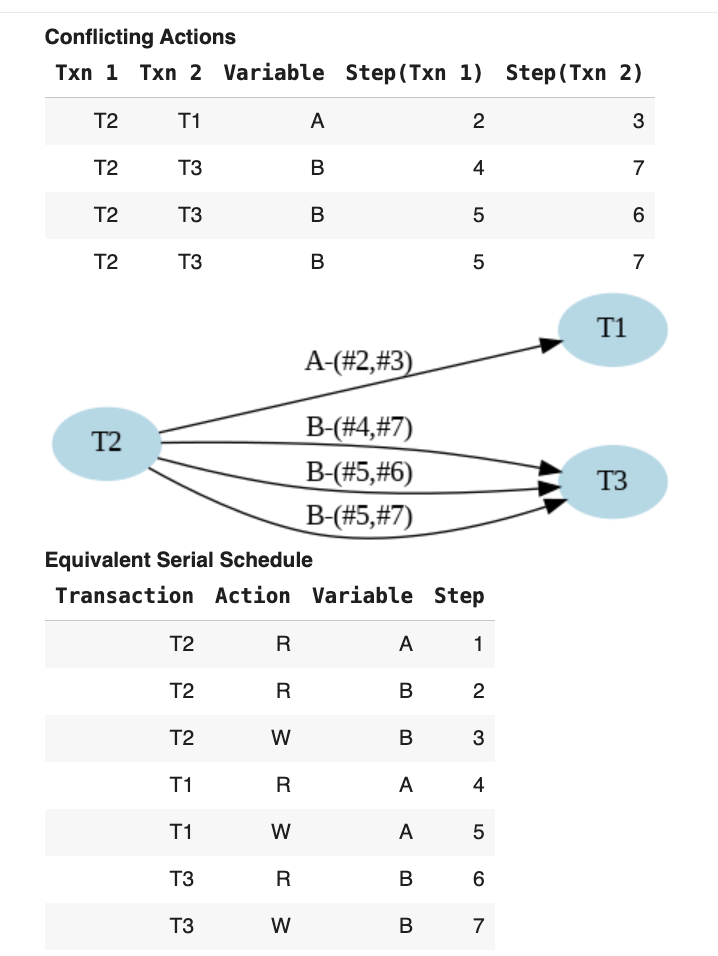

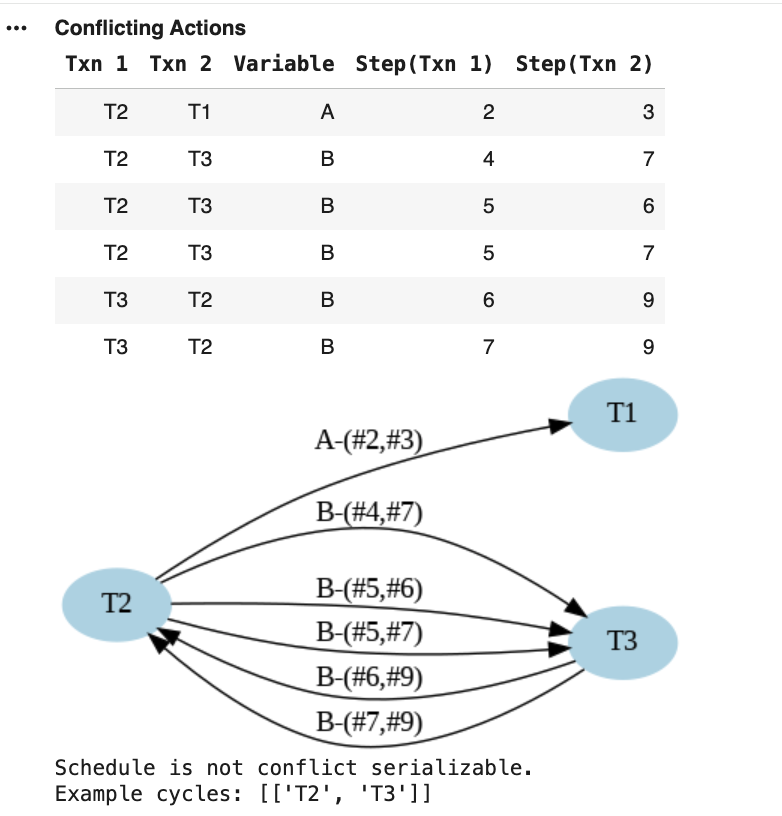

Schedule S2': Our Second Interleaved Schedule

Consider S2', an interleaved schedule. This demonstrates what happens when interleaving creates problematic conflicts.

⚔️ Conflicts Identified

We compute the conflicting actions and the Conflict Graph:

• Critical Issue: Conflicts create circular dependencies

• Cycle detected between T2 and T3

Warning: The conflict pattern creates dependencies that cannot be satisfied by any serial ordering.

📊 Graph Analysis

The Conflict Graph reveals the fundamental problem:

✗ NOT Conflict-Serializable: Not a CS Schedule

✗ No Valid Serial Order: Cannot find equivalent serial execution

The Problem: T2 must precede T3 AND T3 must precede T2 - impossible!

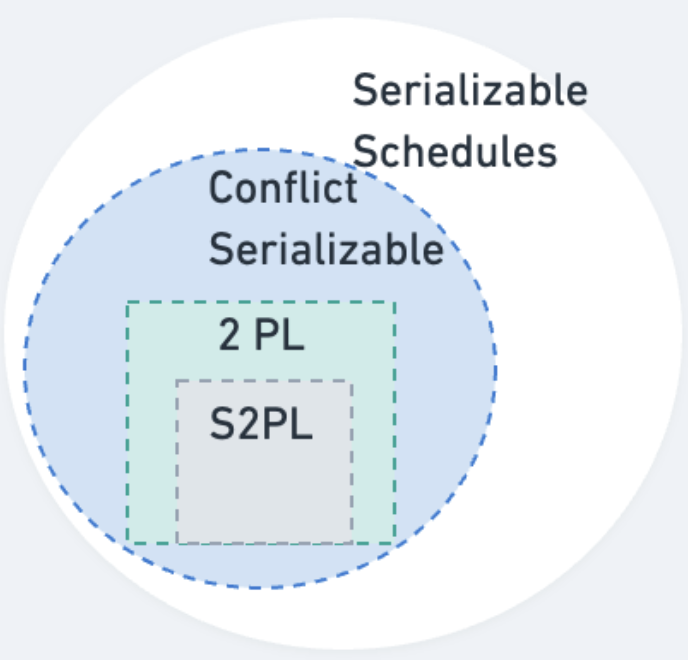

🎯 Important Distinction: CS vs Serializable

A non-CS schedule may still be a serializable schedule, but it's often hard to prove.

The Guarantee: However, a CS schedule will always be a serializable schedule.

Practical Implication: CS is a sufficient (but not necessary) condition for serializability.

Understanding Conflicts: The Venn Diagram

The conflict-venn diagram shows the different types of conflicts that can occur between transaction actions.