Write-Ahead Logging (WAL) 📋

🎯 The logging system

Write-Ahead Logging tracks every change to DB in four synchronized states: WAL log, RAM log, RAM state, and durable DB state.

Understanding the Three States 🔄

Every database operation affects three synchronized states:

📝 WAL Log (Write-Ahead Log)

🔥 RAM State + RAM Log (Volatile)

💾 DB State (Durable)

💡 Intuition: Collaborative Google Docs

Every keystroke → 200ms round trip = terrible lag!

Solution: Edit locally, sync periodically

📝 Google's Revision History = WAL Log

• Tracks EVERY change for weeks

• "Changed 'affect' to 'effect' at 10:32am by Alice"

• Can revert any change, even months later

🖥️ Your Browser = RAM Log + RAM State

• What you see = RAM State (current document)

• Super fast, but lost if browser crashes

• Limited history (last 100 edits)

☁️ Published Doc = DB State

• Auto-saved every 30 seconds

• May lag behind your edits

• Survives crashes, always available

The partial update problem: After editing for hours (thousands of changes), your browser can't hold infinite undo history. Google must sync some changes to cloud even though you're still typing - exactly like databases flushing to disk during long transactions!

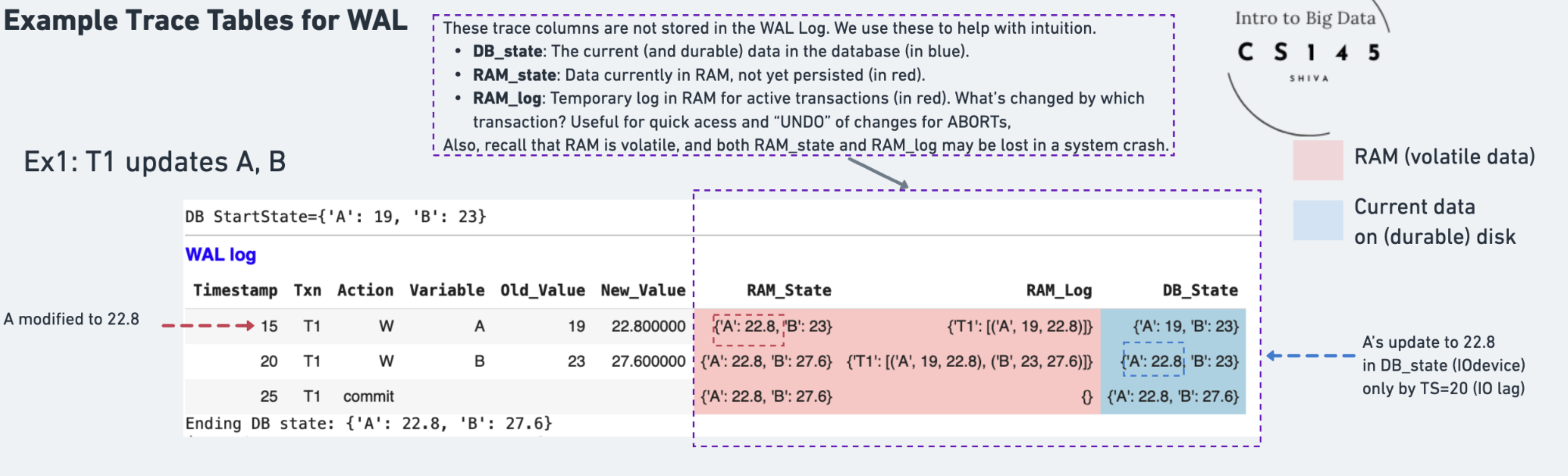

Simple WAL Trace Table: T1 Updates A and B

Example: T1 increases A and B by 20%.

📖 How to Read the Trace

Example: 'A' changes to 22.8 at timestamp (TS)=15

Example: 'A' is reflected in DB only at TS=20

Example: At TS=15, WAL logs "A: 19→22.8 by T1"

⚡ Performance Benefits

Example: "A: 19→22.8, B: 23→27.6, C: 17→20.4..." all go to the SAME log page

Without WAL: Must read page 17 (has A), page 492 (has B), page 1038 (has C)...

Later: Batch apply all changes to their actual pages when convenient

🔄 Recovery Capability

Why WAL's WAL Log is Special: Instantaneous AND Durable

Hardware optimizations make this possible:

- NVRAM (Non-Volatile RAM): Special (more expensive) battery-backed RAM that survives power loss - writes at RAM speed, durability of disk

- Replicated RAM: Write to RAM on 3+ machines simultaneously - if one crashes, others have the data

- Sequential SSD writes: Modern SSDs excel at sequential appends - 100x faster than random writes

The key insight: WAL transforms random updates into sequential appends - the ONE operation that all hardware does blazingly fast!

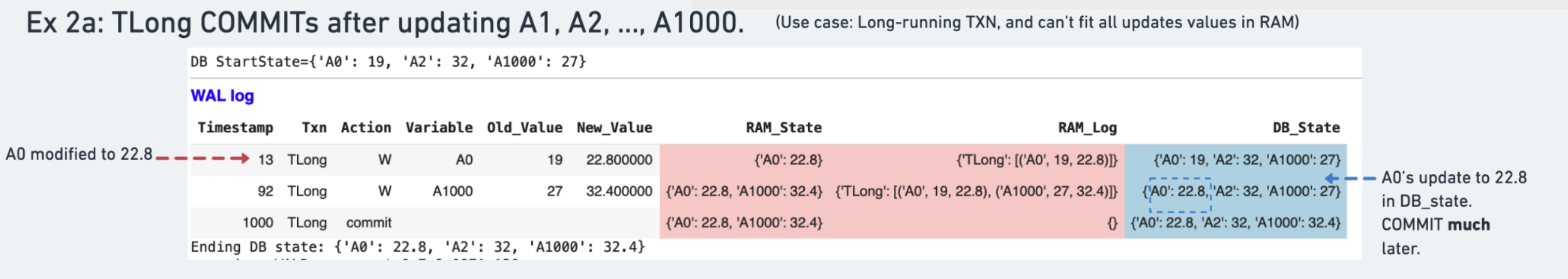

Long-Running Transaction Challenge 🏃♂️

What happens when transactions are too big to fit in RAM?

The problem: TLong updates A1, A2, ..., A1000 but RAM can't hold all changes!

⚠️ Memory Pressure

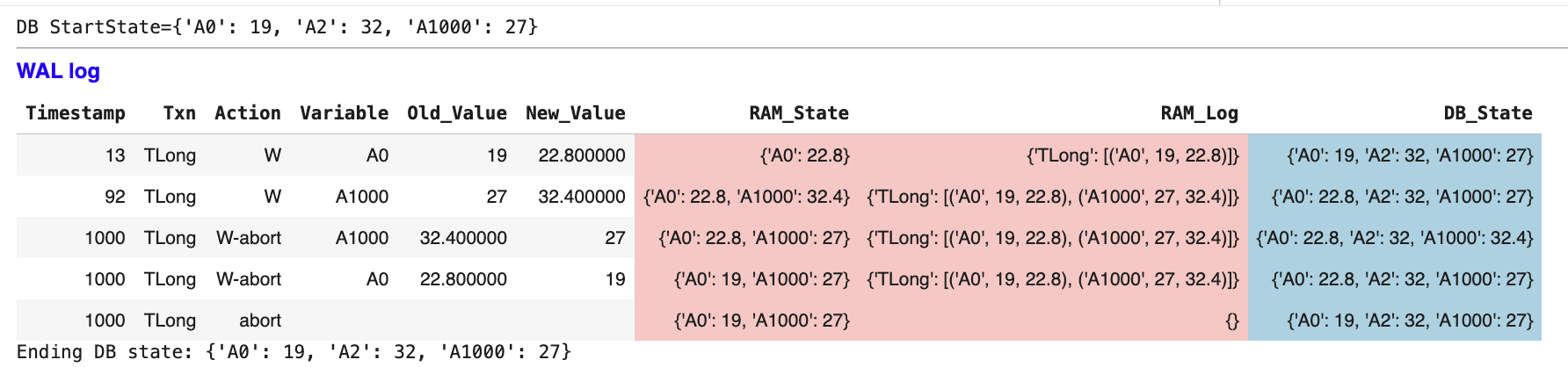

ABORT Scenario: Undoing Long Transactions ❌

What if TLong needs to abort after 1000 updates? [For simplicity, we’ll show ABORTs happening at one time unit. In reality, they’d also span multiple time units.]

ABORT process:

-

W-abort entries: Log UNDO operations for each change

-

Use old_values: A0: 22.8→19, A1000: 32.4→27

-

Update DB_state: Restore original values

-

Final abort record: Transaction officially cancelled

🔄 UNDO Process

WAL Protocol Rules 📋

The Write-Ahead Logging protocol ensures recovery correctness:

🔒 WAL Rules

- Log before data: WAL entry written before any data change

- Force log on commit: All log entries must be durable before COMMIT

- UNDO from log: Use old_values to reverse changes

- REDO from log: Use new_values to re-apply changes

🎯 Recovery Benefits

- Crash safety: Can reconstruct any state from log

- Performance: Changes can happen in fast RAM first

- Flexibility: Support both COMMIT and ABORT operations

- Auditability: Complete history of all database changes